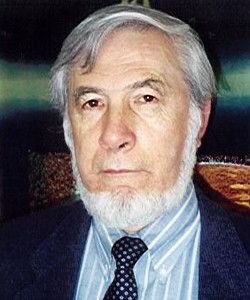

National Academy of Sciences Geophysisist

The following is the transcript form a casual interview with George Gloeckler conducted by The Invisible Lens. This interview covers everything from George's childhood to the present day. Many of the subjects are covered in George's Cinematic Memoir, however, there are many fun and interesting thoughts from George that you may be interested in reading. Very little has been edited. This is the story told from George's recollections. Enjoy!

The following is the transcript form a casual interview with George Gloeckler conducted by The Invisible Lens. This interview covers everything from George's childhood to the present day. Many of the subjects are covered in George's Cinematic Memoir, however, there are many fun and interesting thoughts from George that you may be interested in reading. Very little has been edited. This is the story told from George's recollections. Enjoy!

George Gloeckler was born in Odessa, Ukraine on August 10th, 1937. George’s parents were, father, Walter (Vladimir) Gloeckler and mother, Julia Churgl. Tragically, George's mother contracted Typhoid fever by the time he was 3-years old and passed very suddenly. George remembers his stepmother, Maria, however, to have had a wonderful presence in his life.

Ukraine faced difficult times in the 1940's era due to communist rule. Joseph Stalin, ruled the Soviet Union with an oppressive hand often starving the people to achieve his goals. George and his family, were somewhat shielded from these tactics, however. George’s grandmother, Lydia Gloeckler, took work as a maid for wealthy individuals and was able to bring food home for the family. George's grandmother was his primary caregiver after his mother's death. The family lived in a complex with many other families, including Georges Grandfather Robert Gloeckler, his great Aunt and great uncle, His father’s sister. They all took care of each other.

George passed the days going to the beach at the black sea and walking the big steps in Odessa that led up to the harbor. George has only returned to Odessa once over the years, as it had always been too dangerous for him to return. Georges father additionally advised against a return because of the inability to predict what the Soviets would do in the height of their regime. The fear was that George would be kept there and not be allowed to leave.

During World War II the Germans and Romanians were axis allies. The Germans were able to push the Russians out of Ukraine, and Odessa was then controlled by the Romanians. George recalls that the Romanian rule was not extremely oppressive. They more or less left the people alone to do what they wanted and over the course of the next year. Odessa was thriving. With communism ousted, people birthed their own businesses, including Georges father who was a very entrepreneurial fellow. If it weren’t for George's father, Walter, George would have never have been able to follow the dreams that made him a pioneer and first generation space researcher.

Walter's modest beginnings selling fruit on the street soon parlayed into a movie theatre business. The theatre was a small place that was run by the family. Walter was the manager, and George’s Step-mother, Julia (not yet married at the time) fulfilled the roles of cashier and usher. They started showing German and Russian propaganda films, but quickly realized that there was an insatiable appetite for Western films. The business grew exponentially. George remembers these days fondly.

The Siege of Odessa, also known as The Defense of Odessa, was part of the Eastern Front theatre of World War II in 1941. The Russians returned, and that marked the end of the “good times”. Living in Odessa had become dire and Walter announced that they would be heading west with “their little clan”, which consisted of George, Julia, Grandfather, grandmother, Georges Uncle, his wife and son, Alex who is 10 years older than George.

The Siege of Odessa, also known as The Defense of Odessa, was part of the Eastern Front theatre of World War II in 1941. The Russians returned, and that marked the end of the “good times”. Living in Odessa had become dire and Walter announced that they would be heading west with “their little clan”, which consisted of George, Julia, Grandfather, grandmother, Georges Uncle, his wife and son, Alex who is 10 years older than George.The journey west was an unbelievable one. It started by traveling up the Danube in an overloaded boat under the cover of darkness. Payment for such an escape route was often in the form of bribes. Eventually, the group found themselves in Romania. They camped in a large, wide-open area that was set up for those who were refugees of the war.

One of George’s most vivid memories from this time was derived from an intense emotional experience that happened at an outdoor movie. George recalls sitting on a hill looking down, watching the movie, enjoying himself…and then…the bombs came. The bombs weren’t in the distance, rather, they rained down on their refugee camp. George, through the innocence of a child’s eyes, remembers the bombs lighting everything up, as if it were daylight. The scene was complete chaos. People were screaming, climbing over fences and running for their lives. It was horrific.

With little recollection of what happened next, the family found themselves on a small railway car used for transporting cattle. On the inside of the train they had three levels of bunks for the families to sleep in. It was a difficult journey. When the train would stop the people would rush out with cooking utensils, and quickly make a fire to cook their rations of food. George still can’t believe how these people were able to manage such a task in such short timeframes. He says, “It was amazing”.

Without an accurate representation of time, George and the family reached Poland in 1944. Since Poland was occupied by the Germans at the time, the family was forced to pass through German immigration. Fortunately, Walter, Georges father, was fluent in the German language and was able to talk his way through the immigration and obtain permission for the family to stay in Poland. George's birth mother was Jewish, and so was his great aunt, Cecelia, which would have been a big problem if the Germans found out. As a result, they had to be secretive. George's stepmother was full-blooded Ukrainian with blonde hair and blue eyes and therefore was able to help in the masquerade and secure their stay in Poland.

George remembers the Germans treating them pretty well. Initially, they put all the men into a room, naked, and disinfected them as a group. Then, surprisingly, the family was given a house to live in. It was a beautiful home. George still has no idea why they were given the house, but they were grateful. He insists that the authorities must have assumed that they were German because all the men in the family spoke fluent German. Unfortunately, they only remained in that house for a couple months.

Again, under the threat of a Soviet Union invasion, Walter decided to move the family. This time they were headed to Bavaria, which was controlled by the Americans. They boarded a hopelessly overcrowded train in the capital city of Dresden and started toward Bavaria. There were so many people on the train, they were literally packed on top of one another. This was a time when Germany was bombed excessively. George recalls that the railroadways would be blown apart incessantly, but the Germans would have the tracks repaired in “no time flat”. It was the Germans that kept things moving which made their trip attainable.

Again, under the threat of a Soviet Union invasion, Walter decided to move the family. This time they were headed to Bavaria, which was controlled by the Americans. They boarded a hopelessly overcrowded train in the capital city of Dresden and started toward Bavaria. There were so many people on the train, they were literally packed on top of one another. This was a time when Germany was bombed excessively. George recalls that the railroadways would be blown apart incessantly, but the Germans would have the tracks repaired in “no time flat”. It was the Germans that kept things moving which made their trip attainable.Upon arrival in Bavaria, the family was once again given a home to stay in. This time a farmhouse. George lived here with his father, stepmother, his cousin Eddie and his parents, Albert and Valia. Valia, was from Siberia and was a real Russian. Also with them was his great uncle ________dimar? and his wife and children.

In early 1945, the war was nearing an end. It was obvious that the Germans had lost the war. There was no question. They were drafting everyone from 13 year-old children to 60 year-old men. In fact, Leonard Geiss, George's lifelong friend and collegue, was drafted when he was 14! Fortunately the war ended before Johannes had to serve. George’s great uncle was 60 when he was drafted as well.

Times were bad in Bavaria following the war, and Walter needed work. The family was struggling, so finally, thanks to the Americans, George and the family found opportunity to move to the United States in November 1950. There was an incredibly long waiting list, but finally, they boarded a Kaiser war ship and were transported to Ellis Island in the United States. In order to stay and live in the United States, families had to be sponsored by a group or family with US citizenship. A Baptist Church group in Chicago sponsored and provided housing for George’s family. From Ellis Island they boarded a train and headed to Chicago, IL.

Times were bad in Bavaria following the war, and Walter needed work. The family was struggling, so finally, thanks to the Americans, George and the family found opportunity to move to the United States in November 1950. There was an incredibly long waiting list, but finally, they boarded a Kaiser war ship and were transported to Ellis Island in the United States. In order to stay and live in the United States, families had to be sponsored by a group or family with US citizenship. A Baptist Church group in Chicago sponsored and provided housing for George’s family. From Ellis Island they boarded a train and headed to Chicago, IL.George was 14 when his father Walter started his first job in Chicago as a janitor. Walter soon showed his skill set and was catapulted to becoming an engineer. George admired his father’s work as an engineer and started to find that he had an interest in engineering as well. George “did pretty well in high school” and was the valedictorian of his high school class of 19__.

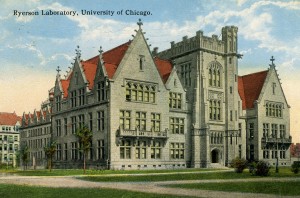

George knew he was not going to be a musician or an artist and looked at engineering as applied science. He knew that in order to succeed and follow in his father’s steps as an engineer, he would need to attend college. George’s family had little money and could not afford tuition, so George started applying for scholarships at various institutions in the Chicago area including IIT, engineering school, and the University of Chicago. The University of Chicago was the first place to offer a full tuition scholarship so he quickly took it “before they decided to take it away”, as he explains. Ironically enough, George discovered they had no engineering school at the University of Chicago, so he did the next best thing and enrolled in the Physics Department.

George knew he was not going to be a musician or an artist and looked at engineering as applied science. He knew that in order to succeed and follow in his father’s steps as an engineer, he would need to attend college. George’s family had little money and could not afford tuition, so George started applying for scholarships at various institutions in the Chicago area including IIT, engineering school, and the University of Chicago. The University of Chicago was the first place to offer a full tuition scholarship so he quickly took it “before they decided to take it away”, as he explains. Ironically enough, George discovered they had no engineering school at the University of Chicago, so he did the next best thing and enrolled in the Physics Department.

While studying at the University, George met his wife, Chris. Chris was incredibly intelligent, possessed many talents, and couldn’t decide what she wanted to concentrate on scholastically. As it turned out, George and Chris were out of sync with the rest of their scheduled classes, however, the two and were placed in a special physics collaborative group established by Professor John Simpson. It was within this small group where the two fell in love and were eventually married in 1958.

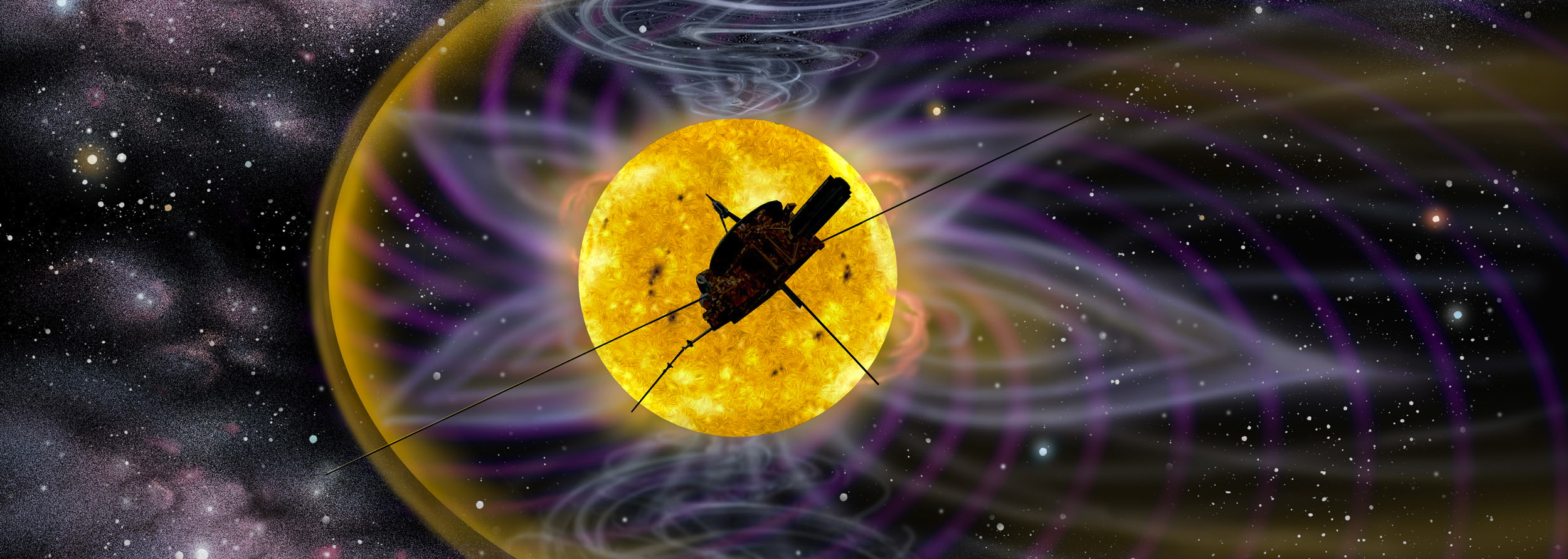

At this time in history, it was still possible for the universities to assemble groups of people for a common goal. In 1966, at age 29, George assembled a group to create a new experiment called the Interplanetary Monitoring Platform or IMP. The idea behind the experiment was to orbit, outside the radiation belt of the earth, and do observations of the sun and its environment.

The IMP had a lot of new technology and many challenges. The IMP was not very big- about the size of a drum. The IMP project was one of the last entry doors for young people to do collaborative work like this at the university level. George wrote the proposal for the IMP with a brilliant scientist, mentor and colleague, Chung Yung Fan. George modestly admits that the idea was mostly his, but with the combined talents of the young men, they managed to be selected.

In 1967, George accepted a position at the University of Maryland, knowing in advance he would have a team, and funding from NASA waiting for him when he arrived. George and his wife moved to Maryland and settled into an apartment. He took a faculty position in the Physics Department, however, his main focus was nurturing the University as a research institution. George was in charge of handling the IMP mission while the University handled the grant which allowed George to purchase things for his experiment. Just like any mandate, George’s responsibility was to deliver an experiment that was tested and calibrated. While he worked out of the University of Maryland, much of the experimentation took place at government laboratories like Goddard Space Flight Center, in Greenbelt Maryland. At the time Goddard managed the entire spacecraft, including George's experiment.

George's specialty was measuring plasmas and energetic particles, or atomic nuclei, like hydrogen or helium, and measuring how fast they go. The data he collected was essential information that was used to figure out how nature accelerates particles and why these elements have such large speeds. George likens this perpetual innate growth to the question - why do the rich get richer?

George hypothesizes “It’s the same physics”. For example, start with a graph that represents peoples income, net worth, or some base line. Then begin with $1000, $2,000 and so forth. Once you start to follow the information collected, you will find that a majority of people will make an average of approximately $50,000. It is here that you will find a peak in the graph, there are others who, of course, make less and many who will make more. So the graph is filled to the peak, but then, instead of being symmetric and going down again in a similar fashion, it has a long tail. It is the same with his findings in accelerated particles. It was from these observations that George began to push the idea of “tails” in his scientific work, because he has seen them. George believes that there is a general principal within this finding, and more importantly tries to determine the physics behind it.

With the collaboration of his colleague, Lennard Fisk, George has proven how nature creates energetic tails. This ground-breaking work proved that tails do indeed exist. Until then, the theory had been frowned upon. Over time these skeptics have indeed seen the tails for themselves, and today there is a general consensus that tails do exist. There is, however, still no consensus on how these tails are made. “How does nature do it?” ponders George. Why do some people become so rich? What makes them so rich? Are they lucky? Do they know how to invest? Why does Donald Trump have 9 billion dollars, or why does Bill Gates have what he has? It’s this line of thought that explains George's work with the IMP.

The IMP measured the distribution of how many particles were traveling slow, and how many were traveling faster. Unfortunately, they couldn’t measure all of the distribution. At that time they did not have data to see “the incomes on the chart”. They could only see the tail. As George created new experiments, he and his team eventually exposed a larger discovery. They were able to identify the poor ones, the rich ones, the ones that were the most concentrated, and, of course, the tails. George found that the tails grew exponentially like the super rich. George and his colleagues discovered that particles have enormous energy and speeds, traveling the speed of light, which can only be measured through momentum.

The IMP measured the distribution of how many particles were traveling slow, and how many were traveling faster. Unfortunately, they couldn’t measure all of the distribution. At that time they did not have data to see “the incomes on the chart”. They could only see the tail. As George created new experiments, he and his team eventually exposed a larger discovery. They were able to identify the poor ones, the rich ones, the ones that were the most concentrated, and, of course, the tails. George found that the tails grew exponentially like the super rich. George and his colleagues discovered that particles have enormous energy and speeds, traveling the speed of light, which can only be measured through momentum.With funding already underway, George assembled his group, which he fondly refers to as “a gathering of the minds”. The collective included electrical engineer Edwin Thoms from Chicago, IL, mechanical engineer John Kane, and a handful of other technicians. George reflects “it was a group that had a common purpose and we had a mission to fulfill…everyone was completely focused and they would do anything possible to make it a success.” If things failed, the group would start over and immediately make it right. This mentality is one that George feels would be hard to duplicate in modern times. Universities are hard pressed to compete with large laboratories like JPL, NASA Goddard, or the Space Flight Center. Back during the development of the IMP, universities were equipped to handle everything themselves. Sadly, that is not the case today.

One of the group’s first tasks at the University of Maryland was to create devices called “Solid State Detectors”. These devices were used to register the speed of atomic particles. These detectors were a commercially new technology and scarcely available. The University of Chicago had perfected the technique of creating these devices and were kind enough to teach George and wife Chris, the chemical process of making the instruments. George recalls, “It was more of an art than science”. With this newfound knowledge, George took the technology to Maryland and began developing the instruments and devices.

Faculty member, George Agante, was said to have experience working with this technology, so George hired him in short order, built a lab, and started building detectors. With this core group and adequate funding, George was able to purchase lab equipment and get right to work. “These days, funding is a little bit different at the University level” says George. “These days many ask for, and get, as much as a half million dollars as a start up cost to build up the infrastructure… I got $5,000 to start my project.” Nevertheless, with George's contract with NASA, he was able to buy the proper equipment and build up the lab. This is not to say everything went smooth. It was an uphill battle to get it working and tested to insure it operated properly. After years of development, George and his team achieved the success they were looking for. They launched and it worked! This successful mission marked the jumping off point for pioneering and space exploration. These achievements led to the creation of the Voyager programs and many other subsequent projects.

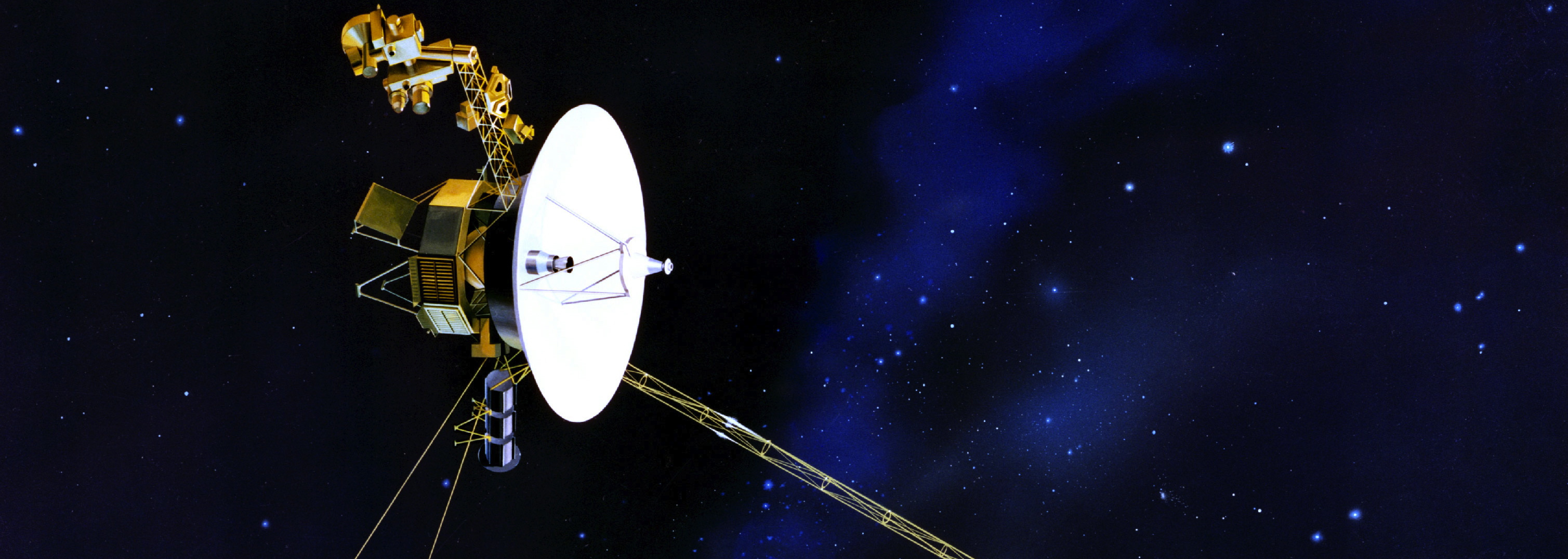

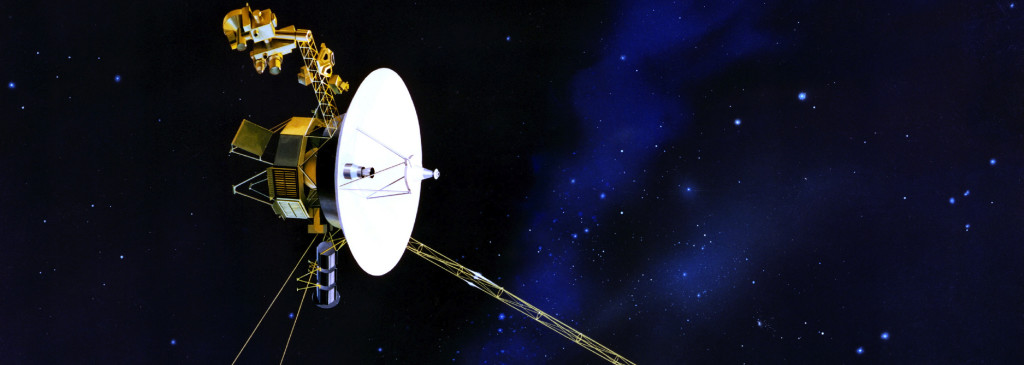

The Voyager experiment was a joint venture with George’s esteemed colleague, Tom Krimigis, in which they proposed new technology for the spacecraft. Again the two faced an uphill battle because there is always a resistance to new technology. NASA was tentative in their investment for fear of failure. Eventually, George and Tom were selected to move forward with the Voyager project. Through many trials and tribulations, in the ninth hour, the men managed to get everything working. George laughs, “I mean literally, people would work around the clock to meet the deadlines and to finish things up and we were no exception.”

The Voyager went on to launch with phenomenal success. The craft had amazing new technology within it; for example, there was a device that would turn an instrument back and forth. Well, anything in space that is mechanical was considered to be something that would fail, and yet, this little device on the Voyager spacecraft has been going back and forth, back and forth, back and forth, every minute, for over 30 years! George states “I never dreamed that this technology would last this long, its unbelievable!" Their persistence to push this technology through, such as to measure very slow particles with low energies, (which had never been done before) propelled the Voyager to making discoveries that would have not been possible without George and Tom’s efforts. This was clearly the second big milestone for George, which led to future relationships with John's Hopkin's APL, or, Applied Physics Lab in Maryland.

George constantly credits the dedication of his team to the success of his experiments. “The people who worked on these experiments were extremely dedicated and completely committed, which was wonderful.” He continues “You have to do these things because there are always problems…you are pushing technology to the limit and physicists must take advantage of any engineering or other technological breakthroughs that they hear about to make all these great things possible.” Transistors and integrated circuits, are a prime examples of this. Today you can launch groundbreaking experiments because of the vast advancement of technology. You need not look any further than your smart phone to see the result of the technology that was developed by George and his colleagues.

Much of society today is ignorant to how important the breakthroughs in space science are to current technology. George says “there are applications all over the world that we would never have today without our technological breakthroughs.” “Of course, we have companies who do a great job developing technologies for commercial purposes, like the iPhone and so forth, but a lot of that was really funded by the government through NASA and other agencies to help everyone in everyday life.” George believes that the science community has the duty to inform general citizens, who are very curious about these things, what scientists find, in layman’s terms, not in a bunch of jargon. “We also need to point out that there is technology that the public can’t even dream of when we perform our experiments.” George feels that we (Americans) are losing the cutting edge with many of these advancements. American scientists were the first to go to the moon, along with many, many firsts. We are not the only nation that can go out to the distant planets and outer space. If you don’t invest in new technology, eventually, someone else will, and it is an incredibly competitive market.

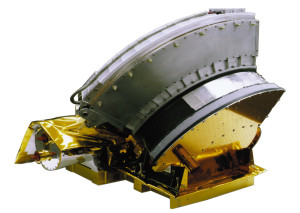

While at Maryland, following the launch of Voyager 1, George and his team started developing instruments called the Solar Wind Spectrometer, or, SWICS that “closed a big gap in their knowledge”. Before this development, it was kind of like seeing the head of an elephant, and seeing the tail of an elephant, but they could not see the actual body of the elephant. Being blind to the full picture in this manner was problematic. To make things more difficult, at that time in history, the team only had access to black and white photographs. With new technology, George and the team were able to put color into the pictures, which made it possible to see the “middle of the elephant”. This was the breakthrough that allowed them to see the entire picture, which was exceedingly important.

While at Maryland, following the launch of Voyager 1, George and his team started developing instruments called the Solar Wind Spectrometer, or, SWICS that “closed a big gap in their knowledge”. Before this development, it was kind of like seeing the head of an elephant, and seeing the tail of an elephant, but they could not see the actual body of the elephant. Being blind to the full picture in this manner was problematic. To make things more difficult, at that time in history, the team only had access to black and white photographs. With new technology, George and the team were able to put color into the pictures, which made it possible to see the “middle of the elephant”. This was the breakthrough that allowed them to see the entire picture, which was exceedingly important.With as groundbreaking as the SWICS project was, it was extremely difficult to get off the ground. George presented several proposals for this instrument, but many were rejected because the technology was simply too much for people to invest in. The team was then forced to develop high voltage instruments that made many individuals skeptical. In addition, George’s team developed very thin films through which particles had to pass, which were thought to never survive. Imagine a carbon film so thin, a few atomic layers only, that you can actually see through. This breakthrough successfully culminated into an instrument that became a joint NASA submission called “Out of Ecliptic Mission”.

The Ecliptic plane is the plane in which all of the planets revolve around the sun. It is very difficult to send a spacecraft out of this plane because everything goes around, including the earth, they all spin in the same way, and to get something out of that plane takes a tremendous amount of energy. The only way we know how to surpass the plane is to go by a huge object, such as Jupiter. When you swing by it in the proper way, that exchange projects the craft either north or south instead of staying within the plane. George recalls that this was a visionary mission that was in the works for decades before it became a reality. There were two spacecraft involved NAMES. The plan was for them both to go to Jupiter, one swinging north over the south pole, and the other would head south by swinging over the north pole of Jupiter. Once on their path, each would make measurements at the same time but in completely different and uncharted regions of our solar system. This mission commanded a great deal of enthusiasm from the space science community. They were headed to new territory in which they could make amazing new discoveries.

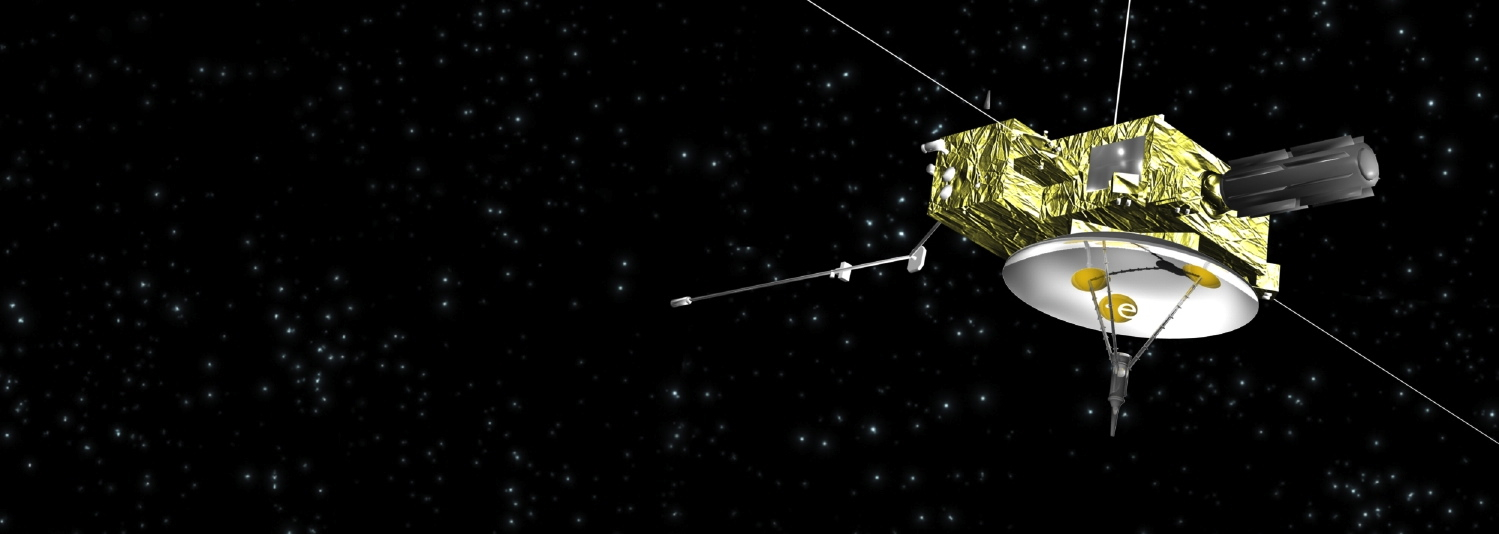

It was during this time that George presented one of his concepts to a well-established, and powerful European physicist, Johannes Geiss. Geiss was the chairman of multiple powerful international science committees and therefore, very influential. Immediately, Geiss saw George’s concept to be a great idea. George recollects “If I were to have done this on my own, it would have never gone anywhere”. Geiss was able to pull all the strings at the committee level, and in a short period of time, Gloeckler’s concept was accepted. The concept was put to test on the European Space Agency, (ESA) spacecraft and everything took off from there. The two built and developed experiments jointly between the United States and Switzerland, as the work was too much for any one group to accomplish alone. Switzerland would take on all the mechanical work in conjunction with the Max-Planck Institute in Germany, who developed all the major electrical systems.

As often seems to be the case, there were budget problems within the Reagan administration that made the project difficult to see through. In one crushing blow, NASA decided to cancel the spacecraft. This decision was not well received by the Europeans at all. After much lobbying and political back and forth, the Reagan administration and NASA stood firm and did not fly the spacecraft. ESA, however, decided to proceed with the project anyway. Eventually, NASA decided to provide minimal help, predominately with the launch of the first spacecraft. As it turns out, since Gloeckler and Geiss’s experiment was placed only on the European craft, it was a success!

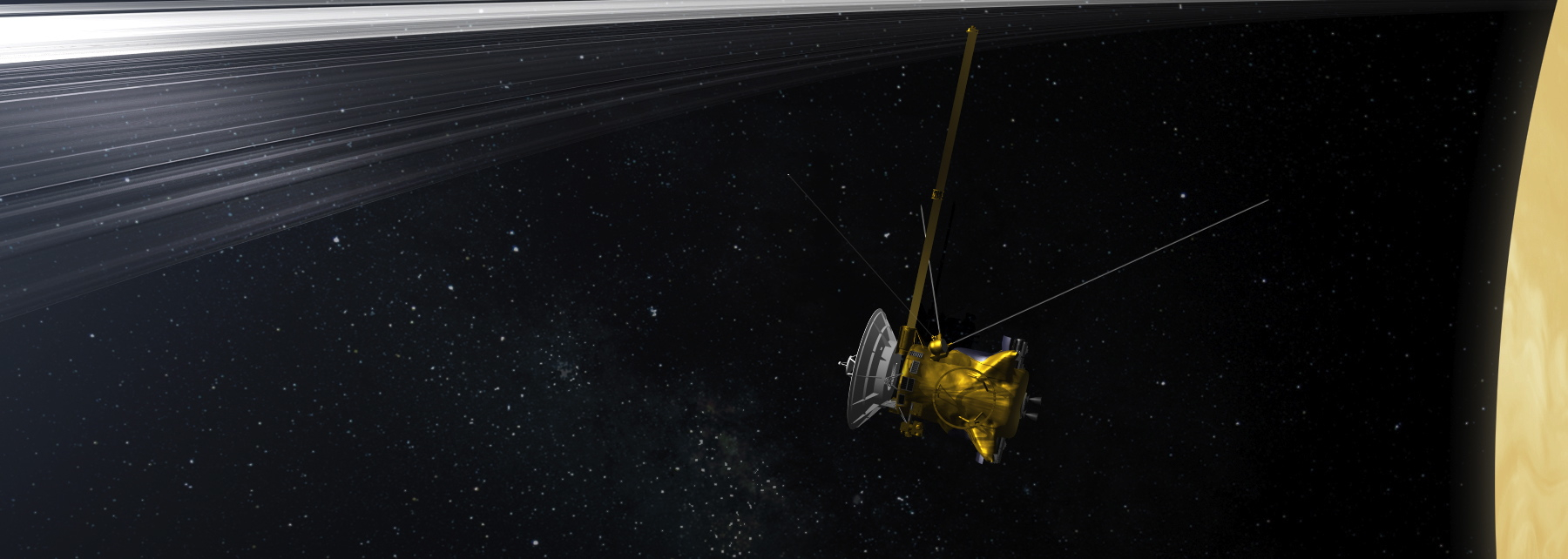

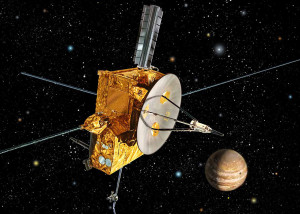

In (year) The European Craft Ulysses was launched, and of course, the entire mission was an enormous success, including the experiments developed by Geiss and Gloeckler. “That was a huge, huge plus,” states George. “How lucky can one get?” These were the biggest projects worked on at University of Maryland and consequently their future projects used the same technology for countless other missions. Many of these missions were done in conjunction with Tom Krimigis from the Applied Physics Lab, (APL) the last of which was Messenger, the first spacecraft to orbit Mercury and send back never before seen photographs to Earth.

In (year) The European Craft Ulysses was launched, and of course, the entire mission was an enormous success, including the experiments developed by Geiss and Gloeckler. “That was a huge, huge plus,” states George. “How lucky can one get?” These were the biggest projects worked on at University of Maryland and consequently their future projects used the same technology for countless other missions. Many of these missions were done in conjunction with Tom Krimigis from the Applied Physics Lab, (APL) the last of which was Messenger, the first spacecraft to orbit Mercury and send back never before seen photographs to Earth.George has since retired from University of Maryland(year) and has entered a new phase of his career as a researcher at the University of Michigan. George now collaborates with acclaimed physicist, Lennard Fisk, spending their time analyzing data retrieved from the Voyager and ACE (Advanced Composition Explorer) spacecrafts. Their findings are reported to Ed Stone at the Jet Propulsion Lab in Glendale California.

George’s new role is to essentially explain observations. Often George uses pictures to illustrate his findings. Pictures reinforce the way things should look or what they should be. It’s much like having a picture puzzle. All the pieces have to fit together to form one cohesive picture that explains everything. The framework is the theoretical work, through the laws of physics that explain the picture that you have envisioned. Simply put, these pictures, backed by science, explain the world around us. These pictures are not always guaranteed. Even with all of the scientific knowledge at George’s fingertips, there is nothing to say that someone won’t come along with a new finding that will change the picture from what we previously believe to be true.

George ponders, “I don’t have a very abstract mind… I need to see things… I love pictures”. Given this to be the case, it’s fascinating that George excels in a field based on theories, predictions, and concepts. Very little of his work is actually seen by the human eye. George says “I see everything in my mind”. With enough information given, George is able to picture theories and concepts in his mind, whether he believes them to be true or not. When fellow scientists approach George with their theories, George will implement the consequences of their picture. “In the end, physics always has to bring you back to reality” says George. “Theories are just theories, they are not God’s truth...unfortunately many scientists have strong beliefs, and even though it violates some stuff, it does not bother them...it’s their religion...Its their picture.” George continues, “A theory is only ok until somebody observes something that does not match it, then you have a problem, and have to change your theory.”

For this reason, George and Lennard Fisk are a perfect pair - of astro physicist and astro theorist. George puts a picture in his mind to determine what would explain his theory. Len, being a theoretician, has to explain it by using the laws of physics and equations that are valid. Len is exceptional at this. Len is equally driven by the desire to want to explain things. This pairing is one that works very well together, but this is not always the case. George states, “some physicists are like applied mathematicians and if it does not solve the problem, that’s ok, they had fun solving the problem. It’s almost like being a philosopher."

In reflecting, George's primary career goal or task, was to provide instruments to perform specific studies to “see the entire elephant”. Essentially, NASA develops a spacecraft, or some other entity, to carry the instruments of experimentation developed and provided by George and his colleagues. Over the years, George and his 1st generation of space exploration colleagues have created a special bond. Physics has the potential to breed great synergy amongst its students. Gloeckler, Geiss, Stone, Fisk, Krimigis and a host of genius level scientists, to this day, still communicate, share theories and analyze research collaboratively. “We are like a family,” says George. “We go to meetings, it’s kind of a social gathering, we discuss things, we argue like hell, but at the end we are all good friends.”

Currently, there is a debate about whether the Voyager 1 has reached interstellar space. A vast majority of the science community, including Ed Stone, head of JPL and the Voyager Mission, believes that the spacecraft has, indeed, left, however, Gloeckler and Fisk believe differently. “We are making progress, but in every meeting, I can feel the walls crumbling. Need complete explanation of this. Who, what, why, etc. Gloeckler and Fisk feel that there could be an end to the controversy as soon as the fall of 2015. George feels that if they are correct in their prediction, that it would be the greatest achievement of already illustrious career. George states, “there’s nothing like making a prediction and having it come true… it’s the Holy Grail”. George continues “this is actually the first time for such a substantial prediction...we believe at this point, because we follow the laws of physics, its all in the physics books, we know we are right.” A majority of the science community, however, sees it differently, has dug their heels in and refuses to consider the dispute.

With there being such well established friendships in their scientific group the question was posed to George, “If you turn out to be right that Voyager has not gone interstellar, will Ed Stone buy you a bottle of champagne or will he be upset?” George replied, “There will be no hard feelings...We never take these things personally... Sometimes we get very emotional about it, and call each other all sorts of names, but on the other hand, everyone has their beliefs and models... Models can be like your baby, you don’t want to abandon them.” Laughing, George continues, “If I am right, I will call him in the middle of the night and tell him I told you so, you should have listened!”

Gloeckler says the great thing about science is that they will always get the story right. They may not always do it the right way, and it may be a long battle with many bad turns, but eventually, they will get it right. Somebody will come along with the right idea that explains all of the observations. Basically, scientists require information. No matter what the study or experiment is, scientists seek facts, however, they never seem to have all of the information, and they are always short. "Obviously we get better as time goes on, but we are always short which results in blind spots. Technology is the key. We can’t wait for technology to come along or we would never get anything done, so it’s a process in which we develop technology ourselves and from which we learn a great deal."

As with every job, community or organization there are often problems within that hold back progress. According to George, collaboration is a huge problem within the scientific community today. George feels that the system is currently set up for mediocrity. Essentially, physicists are following what the science community wants them to do. Currently, there is an army of scientists, most of which are doing incremental work. George theorizes that the community could make the same progress with the top 10 percent of the scientists they have. It seems to be a tightrope. Science needs funding and funding comes from grants. On average, 1 of every 10 proposals are accepted and a scientist's very livelihood depends on the acceptance of these grants. Essentially, a scientist in the current environment is being rewarded for not being creative. George recalls “It got this way when funding became tight…when I entered the field during the Sputnik era, we were going to the moon, money was no problem, I never even gave second thoughts that I would not have a job…but things have changed now.” George continues, “We have become very defensive, nobody wants to stick their neck out because its safer not to.”

George is currently looking for the next “fun thing to do” after Voyager. In George’s estimation, the next step is to go out further than the current Voyagers do. These things take a long time, so the only way to do it is to go into space much faster. To give some idea of scale, if you consider the distance from the sun to the earth, the Voyagers move three times the scale per year. The current Voyagers took 30 years to reach their current position, which is, more or less a lifetime for scientists. To be practical, to go three times further, you have to travel 5 times faster. The technology currently exists, it is attainable, but it takes a lot of push and it needs a big rocket. NASA wants to develop that rocket, but space science's funding is limited now. Science wants someone else to pay for it. George and his closest colleagues want to become the “customer” in this case. George's lifespan would prevent him from seeing this launch, however, that does not discourage him from investing in such a project. Contrary, George and his team feel obliged to push the limits for future generations to come.

In order for this to happen, like everything else, the project needs to be sold. Unfortunately, they compete with many other wants and needs from the science community, so it’s a constant uphill battle. Fortunately, astro physics leaders such as Fisk and Tom Krimigis, who have been to every planet including Pluto (with New Horizon) know how to talk to congress. Of course, George's group does not tackle a project like this for money, they do it for other reasons, and if it weren’t for that, many projects like this would never get off the ground.

The Voyager project, start to present, has been 50 years in the making. This includes selling the project to Congress, development, launch, and mission. These are huge ticket items. Space science is very big science. George states “If you compare us to the National Science Federation or NSF, which funds a lot of science, like regular science, we receive a lot more money…its all politics”

As of August 2015, George has been cited by 2,819 authors. George is aware that he rates very high on the citation index, which translates into the ability to obtain appointments. At this point in his career, he admits he is far beyond appointments, and has achieved everything he wanted to achieve.

George is very proud to be a part of the National Academy of Sciences for over 15 years. The NAS is a very prestigious organization and very few people are elected into the position. In George's particular field, there are only a handful of people that are a part of the academy, including colleague, Len Fisk.

George remembers sitting in a physics department meeting for “Distinguished professorship” and many people were saying how important they were and really promoting themselves, yet he sat quiet. As a result, when he was elected to the academy it was a complete shock! George reflects “here is this quiet guy and when they asked me “what are you doing?” I would reply “I’m working some engineering and some experiments…and suddenly, I was a member of the Academy and that was a BIG shock!” That caused me more pleasure than anyone can imagine!”

George remembers sitting in a physics department meeting for “Distinguished professorship” and many people were saying how important they were and really promoting themselves, yet he sat quiet. As a result, when he was elected to the academy it was a complete shock! George reflects “here is this quiet guy and when they asked me “what are you doing?” I would reply “I’m working some engineering and some experiments…and suddenly, I was a member of the Academy and that was a BIG shock!” That caused me more pleasure than anyone can imagine!”

George admits “I LOVE physics. I love it in a different way than I love my wife, but I love it.” Surprisingly, George ponders that he may have been just as happy being a truck driver or a carpenter, but “now I know I am REALLY happy doing what I am doing.”

Scientists tend not to be “believers” in God often due to the scientific theories that prove creationism. George does not deny there is a God, nor is he sure there is a God. George says, “There is certainly a thing called Nature... There is certainly something there that makes things work... How it happened, I don’t know, but something, somehow, all these things we see, happen... Somehow the physical laws, the chemical laws, all these things are just incredible.” George continues, “I am not a religious person but I certainly have a huge respect for the way nature works in all its complexity.” George believes that it is possible to be religious and be a scientist because he has many friends that are. He, to a degree, is sometimes envious of those who follow religion, as he realizes that it would be very comforting to believe in God.

It has been said that astrophysics is an incredibly humbling profession. George shares this view entirely. "The more you learn about the worlds around us, the more astonishing it becomes, and the more I marvel at the way things have been designed to, somehow, work the way they do, and how smart nature is...If humans were asked to recreate nature, or even a small part of it, we could never do it, its impossible... That’s the astounding thing... In a way, it’s the complexity, and yet, the simplicity of the way nature works that is so mind boggling."

In the grand scheme of where humanity and science meet, George says we may never know the ultimate answers, but we have made a lot of progress. The journey that is not over, however. The process will continue. The more we learn, the more questions we will have because the universe is never ending. It's sort of like medicine for example, we never know everything.

In the grand scheme of where humanity and science meet, George says we may never know the ultimate answers, but we have made a lot of progress. The journey that is not over, however. The process will continue. The more we learn, the more questions we will have because the universe is never ending. It's sort of like medicine for example, we never know everything.George says he will never truly retire from his field of work and harbors no regrets in any way regarding his career. He believes that he would not have done anything different and believes that he is incredibly fortunate to have been led down, or chosen, the right path. “I am very, very fortunate to have done this. I enjoy it, and still enjoy it and have great satisfaction as a result...Some of us just can’t stop, you know. I will die doing what I’m doing.”